Did you know The Godfather Part I was originally released back in 1972?

This September, it returned to Korean theaters through Lotte Cinema. Even more exciting—The Godfather Part II is set to be re-released later this month. (Noted!)

When I first watched it as a child, I didn’t think too much about it—I just enjoyed the movie.

But even then, the experience left a lasting impression on me.

Since it’s such a masterpiece, and also one of my personal favorites, I couldn’t resist going to the theater again after hearing about the re-release.

(Movies should always be seen in theaters—the immersion is on another level!)

As expected, the film was phenomenal.

This time, though, it felt completely different from how I remembered it as a kid—more layered, more powerful, more meaningful.

At first, I considered writing a full review, but the film is simply too vast to cover in one post.

So today, I’ll focus on something smaller: analyzing just one of its legendary scenes.

Because The Godfather truly has it all—story, acting, cinematography, lighting and shadow, editing, and sound.

Nothing falls short. It’s a work of art you must experience for yourself.

The Scene We’ll Examine

The moment I want to focus on today comes around the 57-minute mark of the film’s 175-minute runtime—the legendary cornfield scene.

<Scene Info>

After Don Vito Corleone is gunned down on the street in a conflict between rival families, his life hangs by a thread.

Santino (Sonny), Michael’s older brother, immediately senses betrayal within the family and points to their driver, Paulie, who conveniently called in sick that very day.

Following Sonny’s orders, Paulie is ‘taken care of’

What makes this scene remarkable is not only the location and the backdrop, but also the method of execution.

Each detail adds to the weight of the story—and that’s what we’ll break down step by step.

One of the recurring visual signatures in The Godfather is its low-key lighting, strong contrast, and deep shadows, creating truly striking frames.

The cinematographer, Gordon Willis, was even nicknamed the ‘Prince of Darkness’ for his mastery of shadow and light.

At this point in the story, the Corleone family is weakened after the Don himself has been attacked, leaving Michael’s faction less powerful.

Key members like Santino and Tom are holding a meeting, and the framing emphasizes the Don’s absence.

By placing his desk at the very front of the frame, the camera effectively shows the void left by the Don, highlighting how the central point of authority is gone.

The conversation itself feels chaotic, mirroring the loss of a unifying figure.

This is reinforced through the actors’ blocking: instead of standing together as a group, the four key members (excluding Michael) are paired off, facing each other in two separate exchanges, which visually communicates the disorganization within the family.

Until now, Michael had largely stayed out of family business, and the others largely ignore his input, paying little attention to what he says.

Bored, Michael rises from his seat and begins fidgeting with objects on the Don’s desk.

Santino warns him not to touch their father’s belongings.

This moment is visually and narratively significant: while the other key family members hesitate to approach the Don’s seat, Michael boldly intrudes, almost foreshadowing his eventual transformation into the new Don.

Following Tom’s line instructing Santino to take over if anything happens to the Don, Paulie—the driver who had called in sick on the day of the attack—enters the scene.

Santino interacts with Paulie just as he normally would.

When Paulie coughs, showing signs of illness, Santino asks if he’s hungry and offers a drink, saying it will make him feel better. The conversation is casual and familiar, as if nothing unusual has happened.

However, the moment Paulie leaves, Santino reveals the truth: Paulie is the traitor who betrayed their father, and he orders that Paulie be killed.

Following Santino’s command, the scene transitions into the family’s way of “taking care of” one of their own, showing the cold efficiency of their world.

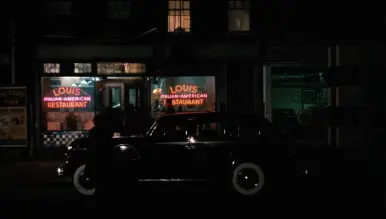

Clemenza asks Paulie if he knows a good spot out West where the family can establish a foothold to expand its influence.

On their way to scout a location, they arrive at the cornfield, where Clemenza has asked to make a brief stop for some business.

While Clemenza attends to his business, a henchman hiding in the back seat shoots and kills Paulie, accompanied by the dramatic music that underscores the moment.

Clemenza and his henchman leave, taking only the cannoli his wife asked him to pick up that morning, abandoning Paulie’s body and the car behind.

At first glance, this scene may appear to simply showcase the calculated and ruthless way the mafia carries out executions, but it also contains subtle details hidden in the background.

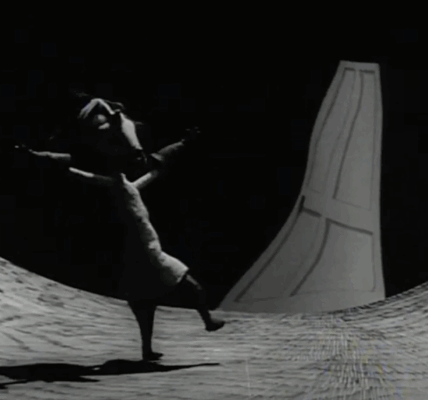

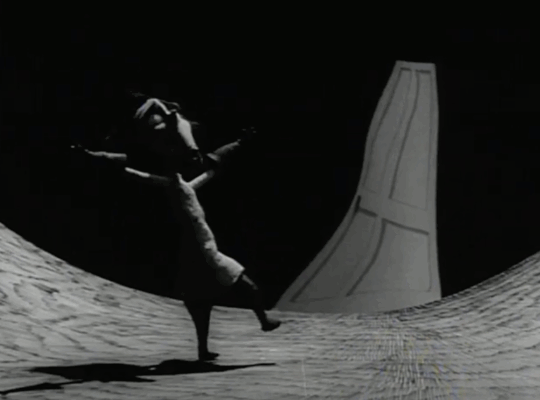

This frame is shot in an extreme long shot.

In the car, you can see a hand in the back seat discreetly aiming a gun at the driver.

Beyond the car and over the cornfield, the Statue of Liberty appears in the background.

The scene clearly establishes the mafia’s method of killing: going to a remote location and carrying out the murder stealthily from the back seat.

But it raises an interesting question: does the Statue of Liberty really need to be in the frame?

If something appears in the frame, its position, the camera angle used to capture it, and everything related to it must carry meaning.

(From Filmmaker’s Eye, p. 2)

Every frame has a reason, and every element within a frame carries meaning.

Why, then, did director Coppola choose to place the Statue of Liberty within this shot?

First, we need to consider what the Statue of Liberty represents.

It symbolizes immigrants, freedom, opportunity, hope, and justice—core ideals of America’s founding.

In the film, the Corleone family is depicted as Sicilian immigrants.

These immigrants came to New York dreaming of the American Dream, but faced numerous obstacles—discrimination, language barriers, political exclusion—that made legal success nearly impossible.

As a result, they created their own world as the mafia, following their own rules.

This scene, which shows that traitors must be killed, illustrates that these immigrants built their own sense of justice and system, separate from American law.

From a personal perspective, I interpret this as Coppola expressing that ideals and reality are not always aligned.

By juxtaposing the Statue of Liberty with the mafia’s execution, the film visually communicates the tension between American ideals and the harsh reality the characters live in.

All in all, it’s truly a remarkable scene, both visually and thematically.

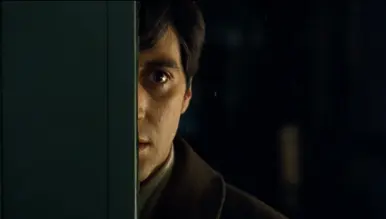

Another notable moment is when Michael visits the hospital where his father, the Don, has been taken after being gunned down on the street.

I’d also like to examine the scene where Michael confronts the police chief and Sollozzo in a tense three-way standoff.

There are truly so many brilliant and exciting moments throughout the film.

With The Godfather Part II set for re-release next month, anyone interested should definitely check it out and not miss it.

That’s it from me for now 🙂

+ Poster I received after watching the movie

(Absolutely gorgeous-!)